Why has the Financial Times become the London Stock Exchange’s bitch? OK, I know the answer already, being that the FT is a British newspaper and all. But still, the LSE has a message to send, and the FT appears happy to be its mouthpiece, and you would think that a serious financial newspaper, even a British one, would be a little more circumspect.

(Ok, ok, stop laughing! I’m serious here! And the Wall Street Journal is NOT a mouthpiece for the New York Stock Exchange! It’s a mouthpiece for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce…)

The LSE is one of the oldest stock exchanges in the world, and one of the most “internationalized” when you look at it as a percentage of the issuers being based outside of the U.K. But over the past decade, the LSE has looked a little frumpy when compared with the NYSE and Nasdaq. It wasn’t nearly as sexy during the high-tech bubble, which was upsetting. But, to add injury to insult, it suffered more from the dot.com bust than did New York. When New York sneezes, London positively catches pneumonia.

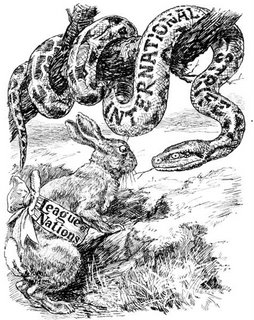

You can see this in the LSE’s valuation. Given its size, over the past two years it has frequently been valued at half of what the NYSE can command, despite New York’s antiquated technological platform. And the LSE repeatedly has been in the takeover cross-hairs. First Deutsche Börse, then the NYSE started thinking about it, and finally Nasdaq shot its credit rating to hell to keep the NYSE out. Basically, when you purportedly are doing so well and your share price is still so low, there is only one real explanation—everyone thinks they can do a better job running the place than you are.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act was a propaganda Godsend for the LSE. It didn’t change the substance of how the world’s securities markets compete, but it did offer the LSE the opportunity to sell itself as a low-regulation market without the fallout that usually comes when you admit that you let issuers get away with murder (or worse—stealing all your investment capital). “No Sarbanes-Oxley” has become its motto, as well as the motto of the U.K. Financial Services Authority. (Actually, the FSA’s motto is “Risk Assessment,” which in the Queen’s English means “No Sarbanes-Oxley.”) Your bond markets are completely non-transparent and you require very little disclosure on bond offerings? Well, we don’t want investors to get confused about all that unnecessary information, and, besides, NO SARBANES-OXLEY! You only bring, at most, 12 enforcement cases each year? Well, we try to take a “light touch” and, besides, NO SARBANES-OXLEY!

The LSE and the FSA make a big deal out of how many IPOs are being held in London these days as opposed to New York, and the Financial Times is more than happy to run these stories nearly every day. But I have yet to see anyone report on whether the actual market capitalization of the London Stock Exchange has increased vis-à-vis the New York Stock Exchange or whether the LSE has gained as a proportion of total world market cap. Otherwise, you are just advertising that, when it comes to Chinese state-owned firms with cooked books, and Kremlin-controlled Russian oil companies, London is the place to be!

The FSA’s “light touch” is so light that they have effectively put the foxes in charge of the hen houses. And while issuers definitely may prefer such an approach, it is doubtful that investors do. Capital markets, in the end, aren’t about attracting issuers, but attracting investors. After all, issuers might not like it, but at the end of the day, they will go where the money is.

(And I know about the LSE’s recent “study” saying that the cost of capital in London is lower than in New York. I believe that one about as much as I believe the City of London’s recent study saying that European bond markets don’t need to be transparent to be as efficient as New York’s. In other words, I don’t.)